Science

New Analysis Confirms Romans Used Hot Mixing in Concrete Production

A recent study has confirmed that ancient Romans utilized a technique known as “hot mixing” to produce their renowned concrete, which exhibited unique self-healing properties. This finding, published in the journal Nature Communications, builds on research conducted by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and addresses previous discrepancies between historical texts and scientific evidence.

In 2023, researchers initially proposed that Romans mixed quicklime with other materials to create a concrete capable of self-repairing. The challenge, however, lay in reconciling this with the concrete recipe outlined by the ancient architect Vitruvius, who detailed construction methods in his work, De architectura, around 30 CE. The latest analysis of samples gathered from a newly uncovered construction site in Pompeii validates the hot mixing technique, suggesting that Romans were indeed ahead of their time in material science.

The core composition of Roman concrete closely resembles modern Portland cement, which consists of a semi-liquid mortar mixed with aggregate. While Portland cement is produced by heating limestone and other materials in a kiln, Roman concrete incorporated fist-sized pieces of stones or bricks as aggregate. Vitruvius recommended using materials like squared red stone, brick, or volcanic rock for building durable walls, emphasizing the importance of thickness in construction.

Admir Masic, an environmental engineer at MIT, has dedicated years to studying ancient concrete. His previous work included pioneering analytical tools to investigate Roman concrete samples from sites like Privernum and the Tomb of Caecilia Metella. In 2023, Masic’s team focused on peculiar white mineral formations known as “lime clasts,” previously dismissed as indicators of poor quality. Their findings revealed that Romans intentionally employed hot mixing with quicklime, enhancing the concrete’s self-healing capabilities.

When cracks develop in the concrete, they tend to propagate through the lime clasts, which react with water to create a calcium-saturated solution. This solution can then either fill the cracks as calcium carbonate or interact with pozzolanic components, further strengthening the material.

Despite the compelling evidence supporting hot mixing, Masic noted a conflict with Vitruvius’ descriptions. “Having a lot of respect for Vitruvius, it was difficult to suggest that his description may be inaccurate,” he stated. The discovery of an active construction site in Pompeii, complete with tools and raw materials, provided critical insights into Roman practices. Masic referred to the site as a “time capsule” that reveals more about the ancient construction process.

The team’s isotopic analysis confirmed that the concrete from Pompeii contained lime clasts similar to those found in Privernum. Moreover, intact quicklime fragments indicated they had been pre-mixed with other dry materials, a key step in the hot mixing process. The volcanic ash used in the concrete also contained pumice, which chemically reacts over time to create new, strengthening mineral deposits.

Masic proposed that Vitruvius might have been misinterpreted, suggesting a reference to latent heat during mixing could imply the use of hot mixing. Inspired by his research, Masic has founded a new company aimed at applying these ancient techniques to modern concrete production. “This material can heal itself over thousands of years, it is reactive, and it is highly dynamic,” he explained.

By integrating historical knowledge with contemporary practices, Masic aims to create a more durable concrete that can withstand natural disasters and environmental degradation. He emphasized that the goal is not to replicate Roman concrete entirely but to extract valuable lessons from its enduring legacy.

This study not only enhances our understanding of ancient Roman engineering but also paves the way for future advancements in construction materials, combining history with modern science.

-

Education3 months ago

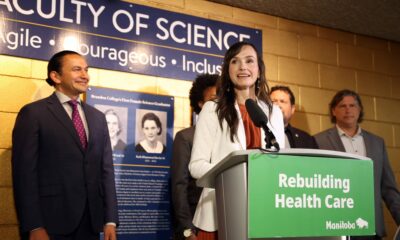

Education3 months agoBrandon University’s Failed $5 Million Project Sparks Oversight Review

-

Science4 months ago

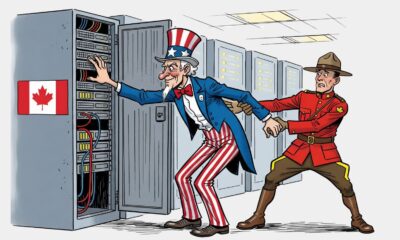

Science4 months agoMicrosoft Confirms U.S. Law Overrules Canadian Data Sovereignty

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoWinnipeg Celebrates Culinary Creativity During Le Burger Week 2025

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoMontreal’s Groupe Marcelle Leads Canadian Cosmetic Industry Growth

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoTech Innovator Amandipp Singh Transforms Hiring for Disabled

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoDragon Ball: Sparking! Zero Launching on Switch and Switch 2 This November

-

Education4 months ago

Education4 months agoRed River College Launches New Programs to Address Industry Needs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGoogle Pixel 10 Pro Fold Specs Unveiled Ahead of Launch

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoRocket Lab Reports Strong Q2 2025 Revenue Growth and Future Plans

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoDiscord Faces Serious Security Breach Affecting Millions

-

Education4 months ago

Education4 months agoAlberta Teachers’ Strike: Potential Impacts on Students and Families

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoNew SĆIȺNEW̱ SṮEȽIṮḴEȽ Elementary Opens in Langford for 2025/2026 Year

-

Science4 months ago

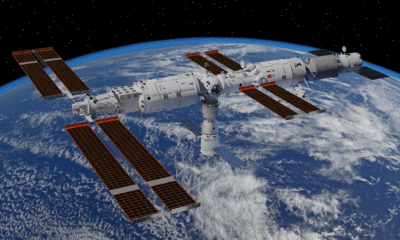

Science4 months agoChina’s Wukong Spacesuit Sets New Standard for AI in Space

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoBNA Brewing to Open New Bowling Alley in Downtown Penticton

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoNew Estimates Reveal ChatGPT-5 Energy Use Could Soar

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoWorld of Warcraft Players Buzz Over 19-Quest Bee Challenge

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoDawson City Residents Rally Around Buy Canadian Movement

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoHuawei MatePad 12X Redefines Tablet Experience for Professionals

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoFuture Entertainment Launches DDoD with Gameplay Trailer Showcase

-

Top Stories3 months ago

Top Stories3 months agoBlue Jays Shift José Berríos to Bullpen Ahead of Playoffs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGlobal Launch of Ragnarok M: Classic Set for September 3, 2025

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoInnovative 140W GaN Travel Adapter Combines Power and Convenience

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoXi Labs Innovates with New AI Operating System Set for 2025 Launch

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoNew IDR01 Smart Ring Offers Advanced Sports Tracking for $169