Top Stories

Canadian Museums Shift Focus, Spark Debate on Historical Narrative

Canadian museums are undergoing significant transformations as they adapt their narratives to reflect contemporary values. This trend, influenced by the Trudeau administration, has led to a re-evaluation of historical interpretation across the country. A recent visit to the Village at Black Creek, a living history museum in northern Toronto, highlights the complexities and controversies of this evolving landscape.

Once known as Pioneer Village, the museum dropped the term “pioneer” last year, citing its potential to hinder reconciliation efforts. The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, the governing body of the village, has embarked on a multi-year project aimed at “decolonization.” This initiative seeks to reshape perceptions of Canadian history by incorporating modern ideals into historical narratives.

Upon entering the village, visitors notice a striking installation in Sherwood Cabin, which has been transformed into a space focused on reconciliation. The cabin’s bright pastel blue interior starkly contrasts with the traditional aesthetics of the surrounding buildings. Inside, a sign indicates that the exhibit reflects the lifestyle Indigenous peoples were encouraged to adopt in the 1800s. While the intention behind this design is clear, many argue that it feels more like a modern imposition than an authentic representation of the past.

An interactive exhibit invites guests to reflect on concepts such as “truth” and “reconciliation.” Tags featuring phrases like “A land acknowledgement is making the invisible visible again” are hung on tree branches, allowing visitors to contribute their thoughts. While engaging, these activities often appear disconnected from the historical realities of the Indigenous communities in the region.

The museum also showcases contemporary Inuit sculptures that seem out of place among the historical buildings. These colorful artworks are intended to illustrate the interconnectedness of all living beings, yet their modern design contrasts sharply with the Victorian-era environment. This raises questions about the appropriateness of highlighting the art of an Indigenous group from a distant region rather than focusing on local First Nations.

In addition to these installations, the village features wire art by Rhonda Lucy, an artist of 2-Spirit Mohawk and Melungeon descent. While these pieces blend into the landscape more seamlessly, they still carry an air of modernity that many visitors find jarring. On the day of my visit, traditional Indigenous weavings created by Métis artist Tracey-Mae Chambers were also displayed, which better aligned with the historical context of the museum, even as they pushed a modern agenda.

The village aims to include diverse narratives, but critics argue its focus is limited. Although plans exist to incorporate aspects of the Jewish experience in Toronto, the current emphasis is primarily on Black and LGBTQ+ histories. Several buildings display stories of Black individuals from the 1800s, while the Town Hall includes a specific section on queer history, featuring figures like Oscar Wilde.

Guided tours highlight the experiences of queer individuals in the 19th century, often attempting to link past identities with contemporary understandings of gender and sexuality. While it is essential to acknowledge the existence of diverse identities throughout history, the museum’s approach raises concerns about applying modern frameworks to historical figures who lived in a vastly different societal context.

The persistence of modern signage throughout the village underscores a broader trend toward sensitivity in public spaces. Bright blue warning signs about potential hazards and environmental factors reflect a desire to accommodate all visitors, but they can feel excessive in a historical setting. This approach may contribute to a dissonance between the intended experience of a historical village and the realities of modern expectations.

Critics argue that the museum’s attempts at “changing the narrative” often come across as tokenistic. The effort to include Indigenous perspectives and other minority narratives, while well-intentioned, may lack depth and authenticity. A more comprehensive understanding of Indigenous life in the 1800s, along with a balanced representation of immigrant histories, could provide a richer context for visitors.

As Canadian museums navigate the complexities of history and contemporary values, the challenge remains to foster genuine understanding without oversimplifying or misrepresenting the past. The Village at Black Creek serves as a microcosm of this broader cultural shift, raising important questions about how we remember and interpret our shared history. Such discussions are vital for moving towards genuine reconciliation and understanding in a diverse society.

The National Post continues to explore the implications of these changes across Canada’s cultural institutions. As the conversation unfolds, it is crucial to engage with historical narratives in a way that respects the complexities of the past while addressing the realities of the present.

-

Education3 months ago

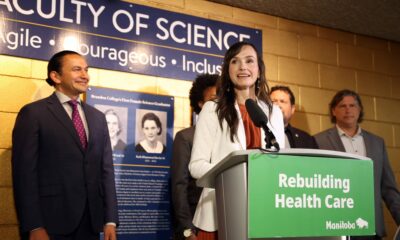

Education3 months agoBrandon University’s Failed $5 Million Project Sparks Oversight Review

-

Science4 months ago

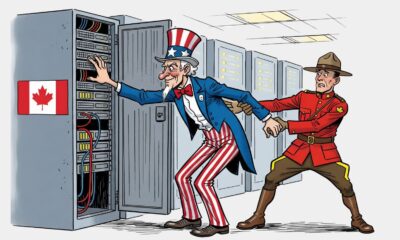

Science4 months agoMicrosoft Confirms U.S. Law Overrules Canadian Data Sovereignty

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoWinnipeg Celebrates Culinary Creativity During Le Burger Week 2025

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoMontreal’s Groupe Marcelle Leads Canadian Cosmetic Industry Growth

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoTech Innovator Amandipp Singh Transforms Hiring for Disabled

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoDragon Ball: Sparking! Zero Launching on Switch and Switch 2 This November

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoRed River College Launches New Programs to Address Industry Needs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGoogle Pixel 10 Pro Fold Specs Unveiled Ahead of Launch

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoRocket Lab Reports Strong Q2 2025 Revenue Growth and Future Plans

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoDiscord Faces Serious Security Breach Affecting Millions

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoAlberta Teachers’ Strike: Potential Impacts on Students and Families

-

Science3 months ago

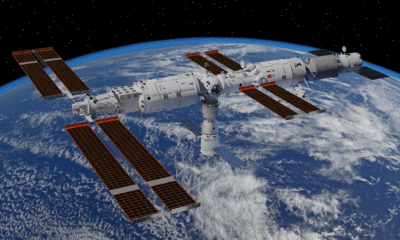

Science3 months agoChina’s Wukong Spacesuit Sets New Standard for AI in Space

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoNew SĆIȺNEW̱ SṮEȽIṮḴEȽ Elementary Opens in Langford for 2025/2026 Year

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoWorld of Warcraft Players Buzz Over 19-Quest Bee Challenge

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoNew Estimates Reveal ChatGPT-5 Energy Use Could Soar

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoDawson City Residents Rally Around Buy Canadian Movement

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoHuawei MatePad 12X Redefines Tablet Experience for Professionals

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoBNA Brewing to Open New Bowling Alley in Downtown Penticton

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoFuture Entertainment Launches DDoD with Gameplay Trailer Showcase

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGlobal Launch of Ragnarok M: Classic Set for September 3, 2025

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoInnovative 140W GaN Travel Adapter Combines Power and Convenience

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoXi Labs Innovates with New AI Operating System Set for 2025 Launch

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoNew IDR01 Smart Ring Offers Advanced Sports Tracking for $169

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoBlue Jays Shift José Berríos to Bullpen Ahead of Playoffs