Science

Indigenous Veterans Reflect on Service and Struggles in Canada

VANCOUVER – Indigenous veterans in Canada have faced unique struggles both abroad and at home, often battling prejudice and exclusion after their military service. John Moses, whose father, Russell Moses, served in the Korean War, emphasizes that the challenges for Indigenous veterans continued long after their return. In 1952, Russell was denied entry to a bar in Hagersville, Ontario, solely based on his race.

John Moses, a member of the Delaware and Upper Mohawk bands from Six Nations of the Grand River, points out that this experience was not isolated. His father, who also served in the navy and later joined the air force, died in 2013. John himself has a legacy of service, being a third-generation member of the Canadian Armed Forces.

“The irony of the situation was never lost on newly returned veterans,” said Moses, who worked as a communicator research operator in the 1980s and later served as director for repatriation and Indigenous relations at the Canadian Museum of History. He noted that these veterans fought for the sovereignty of nations overseas, only to return to Canada where they lacked the same civil rights enjoyed by other citizens.

Indigenous Veterans Day is observed on November 8, highlighting the wartime experiences of Indigenous individuals. Historian Scott Sheffield describes how, for some, military service offered a sense of belonging away from the racism they faced at home. Established as a grassroots movement in Winnipeg in 1993, Indigenous Veterans Day has since gained national recognition, with Sheffield referring to it as a “logical precursor to Remembrance Day” on November 11.

Many might wonder why Indigenous people chose to fight for a country that marginalized them. Sheffield explains that motivations varied by individual and conflict. In many cases, Indigenous fighters enlisted for adventure or economic reasons. However, for others, it served as a political statement. “By enlisting, they were sort of declaring their right to belong, to be part of Canadian society,” he remarked.

One notable figure is Tommy Prince, one of Canada’s most decorated World War II veterans. Sheffield notes that Prince “famously went to war to prove that an Indian was as good as any white man.” His military career was marked by a determination to prove his worth, which he did successfully.

The wartime experiences of Indigenous soldiers often helped alleviate some of the prejudice they faced in civilian life. “If you were sharing a foxhole with a fellow soldier, you only cared about his character and whether he had your back,” Sheffield said. This respect earned through shared experiences became a vital takeaway for many Indigenous veterans.

Yet, upon returning home, the camaraderie often dissipated. Veterans anticipated continued acceptance in Canadian society, but many found themselves facing discrimination once again. Sheffield explained, “They returned home to a Canada where, in many ways, with their uniform off, they were still — in their words — ‘just an Indian again.’”

Many Indigenous veterans who served in World War II also enlisted in the Korean War, perhaps in search of that same sense of acceptance and purpose they had experienced during their service. The federal government reports that over 4,000 Indigenous individuals served in uniform during the First World War, a remarkable statistic reflecting that one in three able-bodied men volunteered. Communities, such as the Head of the Lake Band in British Columbia, saw all men aged 20 to 35 enlist. The Second World War saw the participation of over 3,000 First Nations individuals, though Sheffield believes this number may be as high as 4,300 due to incomplete records regarding ethnicity.

The Canadian government has acknowledged the unfair treatment of Indigenous soldiers, conceding that many believed their sacrifices would lead to improved rights and status in Canada. Unfortunately, this expectation did not materialize, and the lasting effects of this disparity continue to impact Indigenous veterans and their communities.

In recent years, reconciliation efforts have intensified, including initiatives to recognize Indigenous veterans. The Last Post Fund Indigenous Initiative, established in March 2019, aims to ensure no veteran is denied a dignified funeral and burial or a military gravestone. To date, more than 265 grave markers have been ordered and placed, with 24 Indigenous community researchers actively locating unrecognized veterans’ graves.

Floyd Powder, a researcher who spent 32 years in the Canadian Armed Forces, is among those identifying graves of Indigenous veterans lacking headstones. He believes that each marker should reflect Indigenous symbols or language, which acknowledges the service of these individuals and honors their heritage.

Veterans Affairs Canada, which funds this initiative, asserts that recognizing Indigenous Veterans Day does not detract from Remembrance Day. “It instead enhances Veterans’ Week commemorations by shining a spotlight on the tremendous history of Indigenous service,” the department stated.

As November 8 approaches, Sheffield emphasizes the importance of recognizing the mutual respect and camaraderie shared by soldiers, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. These bonds were formed long before reconciliation efforts began, and he urges Canadians to remember this shared history as they navigate the path toward a more respectful coexistence in the future.

-

Education3 months ago

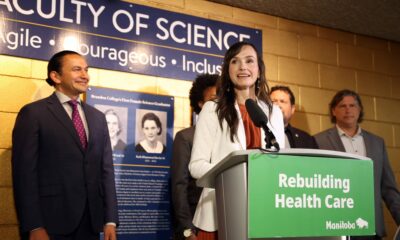

Education3 months agoBrandon University’s Failed $5 Million Project Sparks Oversight Review

-

Science4 months ago

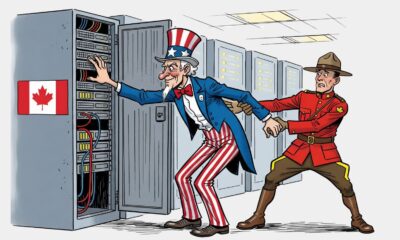

Science4 months agoMicrosoft Confirms U.S. Law Overrules Canadian Data Sovereignty

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoWinnipeg Celebrates Culinary Creativity During Le Burger Week 2025

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoMontreal’s Groupe Marcelle Leads Canadian Cosmetic Industry Growth

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoDragon Ball: Sparking! Zero Launching on Switch and Switch 2 This November

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoTech Innovator Amandipp Singh Transforms Hiring for Disabled

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoRed River College Launches New Programs to Address Industry Needs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGoogle Pixel 10 Pro Fold Specs Unveiled Ahead of Launch

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoRocket Lab Reports Strong Q2 2025 Revenue Growth and Future Plans

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoDiscord Faces Serious Security Breach Affecting Millions

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoAlberta Teachers’ Strike: Potential Impacts on Students and Families

-

Science3 months ago

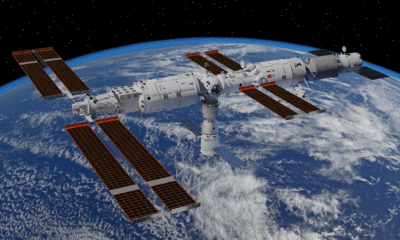

Science3 months agoChina’s Wukong Spacesuit Sets New Standard for AI in Space

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoNew SĆIȺNEW̱ SṮEȽIṮḴEȽ Elementary Opens in Langford for 2025/2026 Year

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoWorld of Warcraft Players Buzz Over 19-Quest Bee Challenge

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoNew Estimates Reveal ChatGPT-5 Energy Use Could Soar

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoDawson City Residents Rally Around Buy Canadian Movement

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoHuawei MatePad 12X Redefines Tablet Experience for Professionals

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoBNA Brewing to Open New Bowling Alley in Downtown Penticton

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoFuture Entertainment Launches DDoD with Gameplay Trailer Showcase

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGlobal Launch of Ragnarok M: Classic Set for September 3, 2025

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoInnovative 140W GaN Travel Adapter Combines Power and Convenience

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoXi Labs Innovates with New AI Operating System Set for 2025 Launch

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoBlue Jays Shift José Berríos to Bullpen Ahead of Playoffs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoNew IDR01 Smart Ring Offers Advanced Sports Tracking for $169