Education

Gwich’in Resilience Offers Lessons in Truth and Reconciliation

In the early 1920s, families of the Gwich’in community in Fort McPherson, Northwest Territories, faced a heartbreaking situation. Anglican missionaries were forcibly taking children, some as young as two, to the St. Peter’s Indian Residential School, located nearly 2,000 kilometres away. This act of separation marked a tragic chapter in Canadian history, remembered through the lens of resilience and collective strength by community members like Elder Mary Effie Snowshoe.

Chief Julius Salu, who had lost his daughter to the school earlier that year, took a stand against this injustice. He declared, “No more. Nobody is to send their children away again.” Salu’s declaration was more than an act of defiance; it embodied the Gwich’in principle of guut’àii, meaning “acting with one mind.” This principle emphasizes collective strength and has been a guiding force for the Gwich’in during the traumatic residential school era.

As discussions around residential schools grow increasingly contentious in Canada, the teachings of guut’àii provide vital lessons in resistance. The strength that sustained Gwich’in families a century ago continues to be relevant as communities confront the denial of historical truths surrounding residential schools.

Understanding Strength in Northern Contexts

In her book, By Strength, We Are Still Here: Indigenous Peoples and Indian Residential Schooling in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, the author explores the concept of strength not as individual toughness but as a communal responsibility grounded in kinship and ancestral knowledge. The experience of residential schooling in the North differed significantly from that in southern regions, complicating the narrative.

Children in the North attended schools like Grollier and Stringer Halls, often traveling long distances. This isolation necessitated resilience through letter writing, sibling protection, and language preservation. Furthermore, the multi-nation student body included Dinjii Zhuh, Inuvialuit, Métis, Inuit, Sahtú, Dënesųłįne, Tłı̨chǫ, and Cree, fostering solidarity that would later fuel pan-Indigenous political movements in the 1970s.

The era saw a stark contrast; while schools in southern Canada were closing, the North became a testing ground for new institutions, some remaining operational until as recently as 1996. The historical context demonstrates that residential schools were not mere errors of judgment; they were systematic attempts to dismantle Indigenous cultures and families.

Confronting Denialism and Emphasizing Collective Strength

The term “genocide” accurately describes the intent behind residential schools, as defined by the United Nations, which includes “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” The evidence gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) highlights both the inflicted harm and the resilience of survivors. Scholar Eve Tuck emphasizes the importance of recognizing both damage and strength in historical narratives.

Despite extensive documented evidence, including survivor testimonies, denialism regarding the severity of residential schools persists. Historian Sean Carleton and anthropology graduate student Benjamin Kucher have noted the increasing visibility of such denialism in public discourse. Denialists often downplay the experiences of survivors, asserting that conditions were not as dire as presented or that the number of missing children has been exaggerated. These narratives not only undermine Indigenous voices but also weaken the broader commitment to truth and reconciliation.

Gwich’in teachings of strength present a framework for resisting this denialism. By reframing survivors as advocates of governance and solidarity, the narrative shifts from victimhood to a celebration of agency and resilience. Chief Salu’s commitment to protect his community illustrates the refusal to accept victimization.

The implications of denialism extend beyond historical discourse; they influence how Canadian society responds to current issues, such as the search for missing children. Calls for “proof” through exhumations can pressure communities to act hastily and overlook the substantial evidence already available.

Surveys reveal a significant knowledge gap among Canadians regarding residential schools. An Ipsos poll conducted in 2024 indicated that while 75 percent of Canadians believe that governments should do more to acknowledge the legacy of residential schools, many still lack detailed understanding. A 2023 survey found that although 73 percent reported familiarity with the topic, knowledge decreased significantly when specific questions were posed. This gap creates fertile ground for denialist narratives.

Moving Forward with Indigenous Strength

The challenge of confronting denialism requires a united front, grounded in the principles of guut’àii. This means prioritizing the voices of survivors, providing resources for families, and intertwining narratives of suffering with those of collective strength. It involves teaching that Indigenous strength encompasses not only survival but also structural transformation.

Children who endured residential schools often went on to lead fulfilling lives and successful careers. Their achievements were not outcomes of the system but rather reflections of inherent Indigenous strengths, such as guut’àii. These concepts are further explored in an upcoming collaboration between the author and anthropologist Sara Komarnisky, titled Talk Treaty to Me: Understanding the Basics of Treaties and Land in Canada. The work emphasizes collective responsibility in understanding the treaties that govern shared lives in Canada.

Chief Salu’s legacy serves as a model for acting with one mind. His promise to stand alongside his community underscores the importance of acknowledging both the harms inflicted by residential schools and the strength demonstrated in the face of adversity. By supporting Indigenous-led truth-telling initiatives and rejecting denialism, Canada can strive towards a future built on honesty, justice, and respect.

In facing denialism today, the narrative of strength is not just about survival; it is about transforming oppression into collective action. By embracing the teachings of the Gwich’in, communities can foster a more informed and equitable society.

-

Education3 months ago

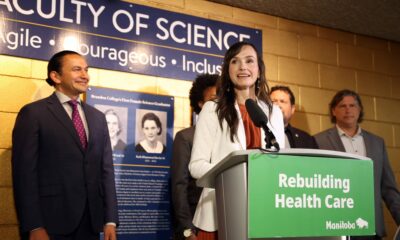

Education3 months agoBrandon University’s Failed $5 Million Project Sparks Oversight Review

-

Science4 months ago

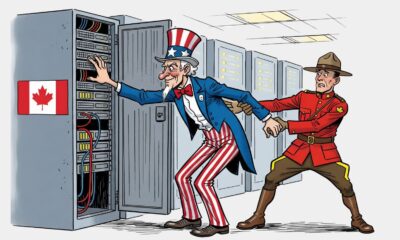

Science4 months agoMicrosoft Confirms U.S. Law Overrules Canadian Data Sovereignty

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoWinnipeg Celebrates Culinary Creativity During Le Burger Week 2025

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoMontreal’s Groupe Marcelle Leads Canadian Cosmetic Industry Growth

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoDragon Ball: Sparking! Zero Launching on Switch and Switch 2 This November

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoTech Innovator Amandipp Singh Transforms Hiring for Disabled

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoRed River College Launches New Programs to Address Industry Needs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGoogle Pixel 10 Pro Fold Specs Unveiled Ahead of Launch

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoRocket Lab Reports Strong Q2 2025 Revenue Growth and Future Plans

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoDiscord Faces Serious Security Breach Affecting Millions

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoAlberta Teachers’ Strike: Potential Impacts on Students and Families

-

Science3 months ago

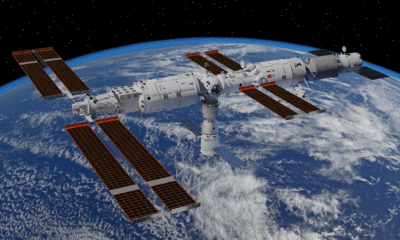

Science3 months agoChina’s Wukong Spacesuit Sets New Standard for AI in Space

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoNew SĆIȺNEW̱ SṮEȽIṮḴEȽ Elementary Opens in Langford for 2025/2026 Year

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoWorld of Warcraft Players Buzz Over 19-Quest Bee Challenge

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoNew Estimates Reveal ChatGPT-5 Energy Use Could Soar

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoDawson City Residents Rally Around Buy Canadian Movement

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoHuawei MatePad 12X Redefines Tablet Experience for Professionals

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoBNA Brewing to Open New Bowling Alley in Downtown Penticton

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoFuture Entertainment Launches DDoD with Gameplay Trailer Showcase

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGlobal Launch of Ragnarok M: Classic Set for September 3, 2025

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoInnovative 140W GaN Travel Adapter Combines Power and Convenience

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoXi Labs Innovates with New AI Operating System Set for 2025 Launch

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoBlue Jays Shift José Berríos to Bullpen Ahead of Playoffs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoNew IDR01 Smart Ring Offers Advanced Sports Tracking for $169