Education

Chiefs Face Criticism Over Governance in Indigenous Education

Internal issues have resurfaced at the First Nations University of Canada, highlighting ongoing challenges related to governance and the intertwining of politics with administration. Critics argue that the persistent control of educational institutions by chiefs has hindered the potential for effective leadership and innovation in Indigenous education.

The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) established three educational institutions in the 1970s, which were meant to be governed by boards of directors composed of chiefs. The intention was for chiefs to set policies while allowing internal administration to manage daily operations. Nearly fifty years later, the same chiefs remain at the helm, leading to concerns about stagnation and a lack of progress in educational governance.

This situation requires a deeper understanding of historical context. When treaties were signed, they solidified the authority of chiefs, providing them with political legitimacy. However, the advent of government control, through Indian agents and churches, diminished the power of chiefs and their councils, rendering them largely symbolic figures. Early leaders like John B. Tootoosis and Walter Dieter worked to empower Chiefs and councils, yet contemporary dynamics have shifted.

As chiefs took on more administrative roles, they risked adopting the very characteristics of Indian agents they sought to move away from. Today, they often find themselves in a neocolonial framework, acting as intermediaries for government funding rather than as true representatives of their communities. While they bear responsibility for the distribution of limited resources, actual decision-making authority resides with the government.

This dynamic has led to a paradox where chiefs are seen as barriers to change rather than facilitators. The FSIN must confront this issue, particularly within their own institutions. A call for a structural overhaul suggests that experienced individuals outside the political sphere should replace chiefs on boards to ensure that educational governance reflects expertise rather than political loyalty.

In 2009, federal and provincial governments mandated changes to the governance structure of the First Nations University of Canada to qualify for funding. However, in 2022, the FSIN reverted to allowing chiefs on the board without consulting funding agencies, raising questions about accountability and transparency in governance.

Historically, chiefs were vocal advocates for their communities, passionately addressing the failures of government. Today, with funding heavily controlled by external entities, there has been a noticeable decline in public protest and dialogue.

Democracy thrives on diverse perspectives and open conversations, crucial elements in traditional governance that involved listening to elders, caregivers, and the youth. Looking to the past may provide essential insights into how Indigenous education can evolve without repeating historical mistakes.

Doug Cuthand, a member of the Little Pine First Nation and Indigenous affairs columnist for the Saskatoon StarPhoenix and Regina Leader-Post, emphasizes the importance of reassessing the current governance model to foster meaningful change in Indigenous education.

-

Education3 months ago

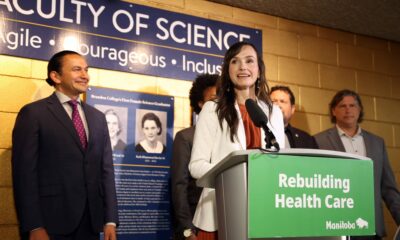

Education3 months agoBrandon University’s Failed $5 Million Project Sparks Oversight Review

-

Science4 months ago

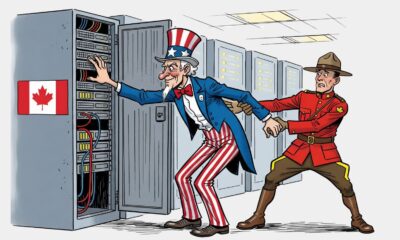

Science4 months agoMicrosoft Confirms U.S. Law Overrules Canadian Data Sovereignty

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoWinnipeg Celebrates Culinary Creativity During Le Burger Week 2025

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoMontreal’s Groupe Marcelle Leads Canadian Cosmetic Industry Growth

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoDragon Ball: Sparking! Zero Launching on Switch and Switch 2 This November

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoTech Innovator Amandipp Singh Transforms Hiring for Disabled

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoRed River College Launches New Programs to Address Industry Needs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGoogle Pixel 10 Pro Fold Specs Unveiled Ahead of Launch

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoRocket Lab Reports Strong Q2 2025 Revenue Growth and Future Plans

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoDiscord Faces Serious Security Breach Affecting Millions

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoAlberta Teachers’ Strike: Potential Impacts on Students and Families

-

Science3 months ago

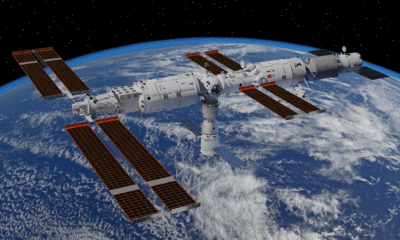

Science3 months agoChina’s Wukong Spacesuit Sets New Standard for AI in Space

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoNew SĆIȺNEW̱ SṮEȽIṮḴEȽ Elementary Opens in Langford for 2025/2026 Year

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoWorld of Warcraft Players Buzz Over 19-Quest Bee Challenge

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoNew Estimates Reveal ChatGPT-5 Energy Use Could Soar

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoDawson City Residents Rally Around Buy Canadian Movement

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoHuawei MatePad 12X Redefines Tablet Experience for Professionals

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoBNA Brewing to Open New Bowling Alley in Downtown Penticton

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoFuture Entertainment Launches DDoD with Gameplay Trailer Showcase

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoGlobal Launch of Ragnarok M: Classic Set for September 3, 2025

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoInnovative 140W GaN Travel Adapter Combines Power and Convenience

-

Science4 months ago

Science4 months agoXi Labs Innovates with New AI Operating System Set for 2025 Launch

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoBlue Jays Shift José Berríos to Bullpen Ahead of Playoffs

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoNew IDR01 Smart Ring Offers Advanced Sports Tracking for $169